How Your Brain Tricks You… Even at 35,000 ft

Some mistakes you see coming, others you feel approaching. And then there are the ones you never see at all—because they happen in your head long before they reach your hands or your instruments.

Cognitive biases: those reasoning glitches that even a trained brain can’t fully escape. In flight, they’re everywhere: in the way you interpret an alert, in the tone of your copilot’s voice, or in the conviction that “the sensor is just acting up.”

Confirmation Bias

I remember a morning departing Orly, heading to Greece—KOS, with its not-so-long runway.

A brief alert pops up: Krueger flaps (no relation to Diane). They’re two leading-edge flaps, named after their inventor. A nuisance alert, as we say in the business—too brief to process, often assumed to be a glitch or a momentary misread by the system.

Fault lights? At that point, everything was normal.

Add to that a long streak of incident-free flights, a growing trust in your aircraft… and you have every condition for falling into confirmation bias: “Everything’s fine, let’s continue.”

The bias quietly checked its box: bending reality to match what you want to believe.

We kept taxiing. Lined up on the runway, the alert came back—this time persistent.

The indication said the flap was deployed, but the alert said the opposite.

It no longer mattered which one was correct: we had to abort.

Back to the stand. Mechanics came on board: flaps OK, faulty sensor.

New flight plan, more fuel… and passengers facing a longer delay than expected.

The Brain’s Automatic and Adaptive Modes

Simplifying a bit, our brain works with two modes: automatic and adaptive.

Learning and repetition transfer skills into automatic mode, making them effortless to access. Meanwhile, adaptive mode—just like its name—deals with new situations. It also supervises the automatic mode, and under normal conditions, the two complement each other.

➡️ Automatic mode DOES. Adaptive mode THINKS.

Great for flying—until something unexpected slips in.

Because in situations of stress, hunger, cold, or fatigue, the brain instinctively prioritizes automatic mode, with all the possible errors that come with it.

A warning light appears, you interpret it too quickly (in automatic mode), and your entire reasoning builds on a false foundation.

Confidence vs. Competence

This is probably the most universal bias.

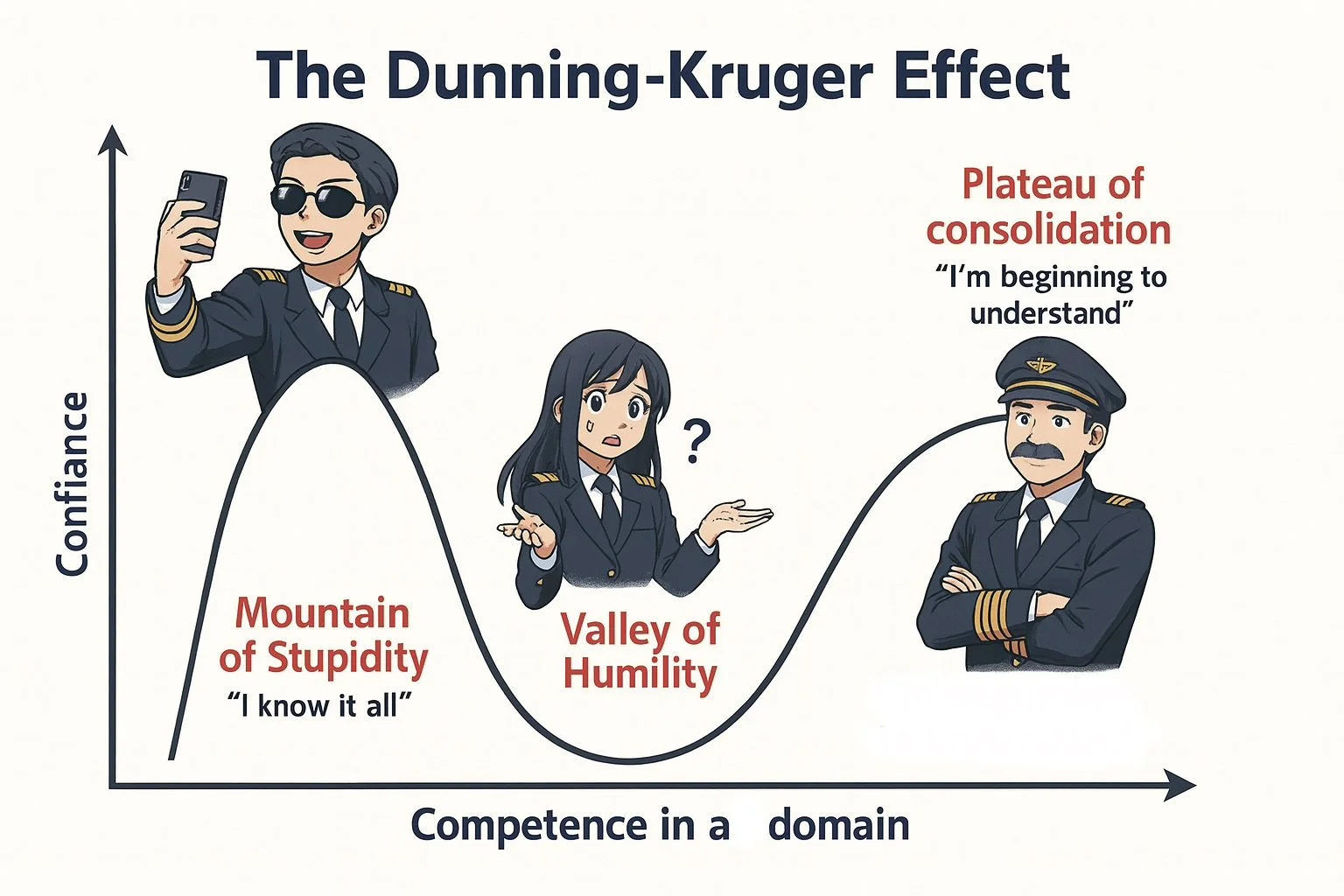

The Dunning-Kruger effect (yes, another Kruger—still no relation to Diane) describes the curve where confidence skyrockets long before competence does.

You finish your type rating, your FM is spotless, your first engine failure in the sim went smoothly… and you think you’re ready for anything.

In reality, you’ve just reached the “peak of certainty” and the infamous mountain of overconfidence.

You launch your Instagram account, you talk about your life as if you’ve mastered everything—without realizing you still don’t know much.

Many pilots hit this stage around 1,000 hours on type. You know the aircraft well, your routines are solid.

And that’s often when reality catches up: an unusual failure, unexpected weather, a colleague less comfortable… and you realize how fragile your confidence really was.

Dunning-Kruger can’t be cured. It’s something you must go through.

Real competence begins when the curve drops again and your confidence returns to its rightful place.

Time, humility, and intellectual honesty will slowly lead you toward true mastery.

Tunnel Vision and Mental Optical Illusions

Under stress—or under excessive workload—our perception narrows. The attentional field collapses, sometimes to the point of missing the essentials.

I remember a flight to Rome: a 15-kt crosswind on the ATIS, nothing serious. Descending through 5,000 ft, we change frequency… and the tower now announces 45 kt of crosswind for runway 16L. Several small storm cells had formed between the ATIS update and our approach. I remember perfectly the moment my copilot and I tunnel-visioned for 15 seconds: “No way, he didn’t say 45 kt crosswind!”

Go-around, of course. A saturated frequency, storm cells popping up like popcorn on the radar, calls, checklists, coordination…

That kind of overloaded phase narrows your vision and can make you forget a vital item. There’s only one solution: slow things down under pressure, breathe, and focus on the essentials.

CRM as the Antidote

A well-known vaccine against these biases is crew teamwork. Not because another brain is better than yours, but because it sees differently.

That’s what Crew Resource Management is: illuminating the blind spots of the human mind. A good copilot isn’t the one who agrees with everything, it’s the one who dares to doubt out loud.

The other vaccine is self-awareness. It’s no coincidence that it sits at the center of our competency model. Self-knowledge, mental modes, the traps they provoke…

and more broadly: understanding your weaknesses, your defaults, and learning to be cautiously skeptical of yourself—in the positive sense—to keep improving.

Final Approach

Our worst mistakes aren’t the ones we make, but the ones we never see coming or the ones we stubbornly refuse to see. The ones our brain justifies, disguises, rearranges so everything still feels coherent.

In flight as on the ground, learning to doubt may be the greatest skill we can develop.

Aristotle said: “The ignorant assert, the learned doubt, the wise reflect.”

In aviation, all three sometimes fly together. But the one who gets home safely is often the third.

We finally found the third Kruger of that blog! Wait , I know this pilot on the right?